You are reading the book Wicked Problems, published by Jon Kolko in 2011.

An Introduction to Wicked Problems

A Designerly Approach to Social Entrepreneurship

Designers can change culture, change behavior, and advance a system of values, and social entrepreneurship provides the economic vehicle in which designers can tackle wicked problems. For example, looking at a problem such as obesity, let's compare a scientific approach with a designerly one.

The scientific approach would use objective knowledge to produce optimal behavioral rules, with the expectation that people would follow those rules to reverse their obesity. Objectively, obesity is related to genetic dispositions, quantities of nutrients consumed, levels of physical exertion, and more. The nutrition component can be treated like an equation, with the various data of a human beings turned into an algorithm to produce the optimum diet. Exercise can be planned in a similar fashion to calculate sufficient burned calories or the ideal pulse rate. The scientific approach provides an objective "right thing to do"—eat this much of that, exercise this much. But getting people to do the right thing often proves difficult for a host of reasons, including established cultural norms, poor education, peer pressure, lack of financial and geographic access, lack of time or will power, and more. A designerly approach looks for factors that contribute to negative behavior and tries to shift them through some form of designed intervention. The constraints for the designed intervention include the cultural norms, access to education, the physical and financial access of the users, and all of the other qualities that acted as barriers to the more objective or scientific approach.

For example, looking at culture, you would find that the highest rates of obesity occur among population groups with the highest poverty rates and the fewest years of education. So a design team might spend time in these communities, observing, interviewing, and interacting with their residents.

Drewnowski, A, and SE Specter. "Poverty and obesity: the role of energy density and energy costs." American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 2004: 6-16.

The team would look for factors beyond the nutritional qualities of food, such as access to fresh food: For example, the team may identify only convenience stores in a neighborhood with few residents who have cars. Introducing a transportation program to community gardens and larger supermarkets could lead to positive behavior.

Or the team may find a culture with century-old habits that we have only recently discovered to be harmful—such as daily bacon or food cooked in fatback and lard. In this case, the strategy might include low-cost or free access to alternative cooking oils, such as olive oil, as well as education and time.

Or the team may meet people who don't know about the relationship between their health and the food they consume. An appropriate response might be free educational programs at community church or school sports events.

One quickly learns that wicked problems such as obesity demand both a scientific approach and a designerly approach. Because "every wicked problem is a symptom of another problem," any wicked problem is too big for a single-tiered approach. Poor people in the targeted communities don't have fresh vegetables because their neighborhoods don't have stores that sell them. That's an economic problem. They don't drive to other areas because they can't afford cars. That's also economic. They can't take the bus, because the city voted for the bus line to serve only other, less impoverished areas. That's a policy issue. The city voted that way because more voters live in more affluent areas. Now we're back to economics. And residents of more affluent areas are more likely to vote because they learned the democratic process (education), whereas poor people might have missed those lessons because of inferior schools in their districts, which again come down to economics.

A "designerly approach" embraces a methodical and often exhaustive form of craftsmanship, achieving success through informed trial and error. This approach empathizes and reflects; it has an intimate view of people's aspirations and emotions. Several vivid examples of design-led culture change illustrate the power of this approach.

The examples of Movirtu and Studio H describe "design-led social entrepreneurship"—situations where designers (as compared to technologists or business owners) have assumed leadership roles to create positive social change.

Cultural Change in Developing Countries

Movirtu is a startup that supplies phone service to rural and poor parts of Africa; its typical users, making less than two dollars a day, can't afford a phone. They buy an access card from a street vendor and use it with a borrowed or public phone. Users of the system interact with fairly basic technology (spoken menus and standard keypads, with no touchscreens or smartphones). In developing this system, the design team sought to understand how the users consider the role of a mobile phone in their lives. Two designers spent weeks in Nairobi to do research and test and refine prototypes. One of the designers, Ashley Menger, found that, for many users, "You have no address, no phone number, no way for people to find you. Facebook and phone numbers are like an address." A phone gives "access beyond where you walk each day—to news, mPesa (a mobile-phone based money transfer service), education. There is a sense of connection with world around you, and ultimately empowerment."

Foster, Dave. Movirtu and frog design team up to create “telecom cloud.” May 21, 2010. (accessed November 14, 2011).

Menger said that design research was instrumental in gaining even simple understanding and empathy. "Among the people I've interviewed for [other] research projects, there is generally some baseline for a shared experience.... This was the first time where the gap in experience felt almost insurmountable. Could I really understand the mobile phone needs of a woman living in an African slum with two children, ...no running water, sparse electricity, scant food, and in fear of thugs?" Ultimately, Menger and her team were able to gain both understanding and empathy through a number of the methods described later in this book.

Menger, Ashley, interview by Jon Kolko. Personal Email (November 26, 2011).

Cultural Change by Small Businesses

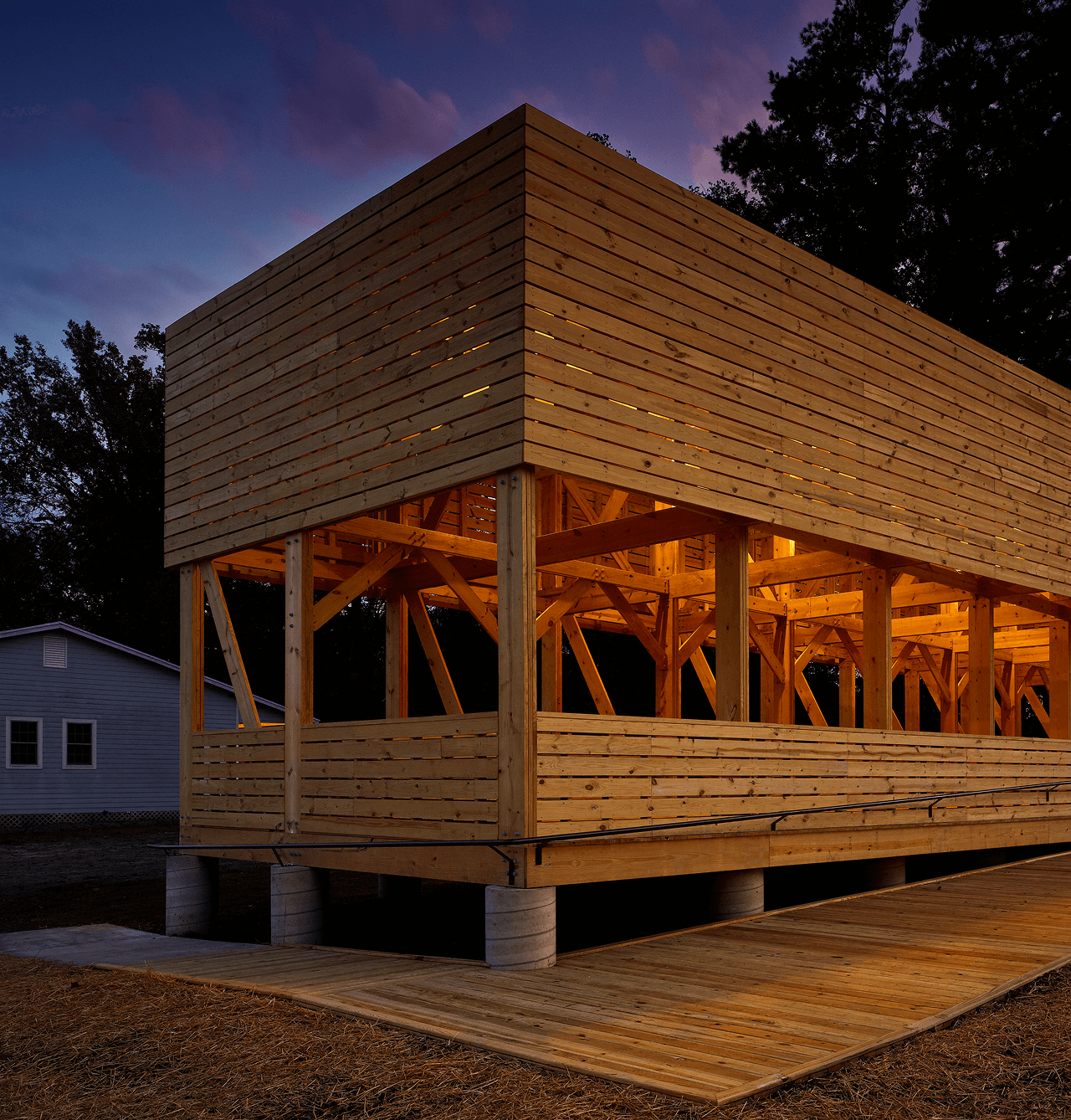

Studio H is a one-year program for juniors in Bertie County, N.C., one of the poorest communities in the United States. In this county, one in three students live in poverty and 95% of public-school students qualify for free or discounted lunches. The Studio H program is a unique example of design-led social entrepreneurship in action. It combines "a more abstract, experimental, fun, and subjective learning platform" with building skills such as "the confidence to try something new, the ability to think through a problem and to frame a problem in a new way, and to accept the notion that design is inherently about a chaotic magic in which the solution is almost never as concrete as, say, an algebra equation," writes Emily Pilloton, the program's designer.

Pilloton, Emilly, interview by Jon Kolko. Personal email (November 2, 2011).

While a more typical approach to educational reform might try to shift policy by changing curriculum standards or changing incentives for teachers, a design-driven approach uses research to understand a larger picture of education. Design-driven innovation reframes the problem and offers solutions that offer both utility and emotionally positive changes. Studio H tackles the "wicked problems" of education and poverty by using design skills to build confidence and personal awareness in students who typically could not have escaped their low-income environment.