You are reading the book Wicked Problems, published by Jon Kolko in 2011.

Teaching and Learning

A Curriculum Template

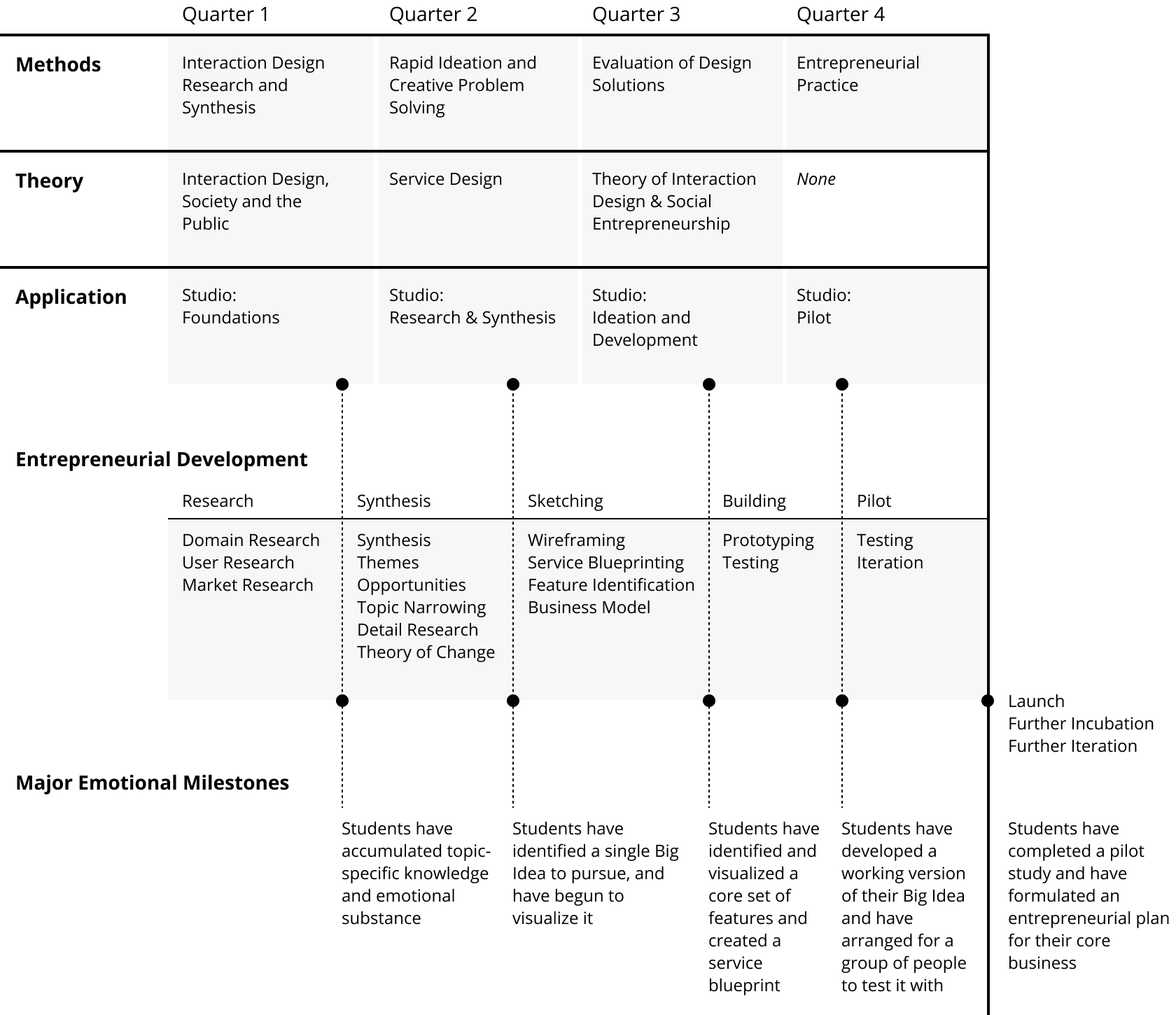

The following social-entrepreneurship and design curriculum can be taught to—and applied by—students with little or no background in design (or engineering, marketing, or any other "making" discipline) in the context of large-scale social problem solving. The program is a work-in-progress and is not the model of design education for the future. But it is one model of design education for the future, it has experience-derived features, and qualitative evidence supports it as a strong pedagogical approach for other institutions to build upon. These other institutions need not be limited to colleges and universities; the curriculum's materials can help to prepare grade-school students for literacy and fluency in a changing world. Nor must the institutions be "academic"; a corporation or consultancy can teach the materials internally or use them to help clients understand the process of designing for impact.

The curriculum departs from the three traditional educational models described above in a number of key ways. Students engage in traditional graduate programs to gain skills, knowledge, inspiration, and contacts. In addition to these common goals, this curriculum teaches students how to start a company with a "double bottom line": focused on both operational self-sufficiency and social impact. Students identify an opportunity for impact, develop systems and products that drive value, produce working prototypes, learn the basics of company operations (including budgeting, sales and marketing, and branding), and focus on creating an entity that is financially self-sufficient, so they can pay themselves the salary they want while they do the work they want to do.

The program explicitly pairs classes in methods ("how to" classes) with theory classes to encourage constant reflection related to the nature of social change. Students learn to understand systemic consequences and to act with a sense of purpose and responsibility in their design decisions. Although both are critical in any design program, they're of utmost importance in a design program focused on changing behavior: Students graduate with both a massive amount of power and a sense of humility about how to wield it.

This program provokes debate and reflection by presenting alternative, conflicting, and often-extreme viewpoints through readings and an influx of guest speakers. Students are forced to develop a Theory of Change related to their core business and to constantly challenge and evolve this theory.

Formal Outcomes and Assessment Tools

Like other curricula, this program measures success through a set of outcome statements which describe skills students should have acquired by the time they complete this curriculum. Students self-assess their progress towards these outcomes four times during the academic year and then get back their self-ratings when they graduate. And every week students film video-reflections on entrepreneurship and their academic study.

As a result of completing this program, students will be able to...

Demonstrate a comprehensive process for solving complicated, multi-faceted problems of design.

Our students learn a process of design that can be applied to any type of problem. In demonstrating their competency, students need to be proactive and to understand what action to take at what point in the process. This is learned through experience; students begin by following a process in a rote manner, but they slowly learn to customize the process for their unique design problem.

Develop original design approaches to large-scale social problems.

Students learn to direct their design efforts towards problems that have a meaningful impact on society. This implies design judgment—students learn to articulate a value structure and judge design problems within the structure's context.

Develop a unique vocabulary of criticism as related to technology.

This allows objective and comprehensive responses and critiques to large-scale design problems. Our emphasis on mindfulness requires our students to examine design opportunities and solutions from a critical perspective. This requires students to understand the unique context in which a design opportunity exists, build relationships and empathy with stakeholders, and offer a thoughtful opinion on the existing and desired state.

Demonstrate the creation, application, and verification of new forms of design research that improve on the state-of-the-art.

While our students learn existing and leading design research methods, they quickly begin to see shortcomings in these methods as applied to social and humanitarian research. As a result, students must craft their own research methods and successfully apply them with users and other constituents.

Develop and document new models to present various types of qualitative data.

As students gather large amounts of research data, they are challenged to present this material in ways that clearly describe the research and help the audience form an educated opinion of the material. This results in a highly visual model of the data and its interpretation.

Develop original synthesis forms that re-contextualize familiar thought patterns.

Fostering innovation and extracting insights demand assigning meaning to the gathered data. Students learn to create their own synthesis forms—often large-scale documents, maps, charts, and diagrams—to extract the most value from research activities.

Develop original methods of framing issues, resolving conflict, and parsing complex situations into actionable objectives.

Conflict generated during design is often productive and critical for advancing the quality of a given idea. Students learn methods for engaging in productive design criticism and conflict; they are expected to create their own frameworks for judging ideas and resolve contradictions within the context of a design activity.

Cultivate a culture of speed in the creation of demonstration prototypes to stimulate the collaborative process.

Students learn to quickly represent their intent and to communicate their designs to stakeholders and to receive criticism on the ideas. Fundamental to this outcome is the idea of designing publicly; students are constantly pushed to work confidently with and around other people in a studio environment.

Create interactive working prototypes of digital design problems that allow for comprehensive user testing and the communication of diverse and complicated ideas.

Students are expected to constantly evaluate their design solutions by gathering data from end users. During the project's pilot phase, students must present a working prototype of their solution, system, or service for comprehensive user testing. In many cases, students are urged to pilot test a simple and small piece of a larger solution.

Compose scholarly documents of publishable quality that explore the nature of design and rigorously defend the assertions used to construct the argument.

It's critical that students be able to intellectually reflect on the impact of their design work; scholarly contributions allow students to participate in the larger discourse related to designing for impact as they allow other designers to build upon the knowledge created during the design process.

Participate in the global design infrastructure that exists within the business and academic world.

Professional conferences, publications, and other engagements give design students the opportunity to reflect on their own situation, process, and methods—and compare their learnings and accomplishments with those of their peers and industry mentors.

Invent new forms of behavioral prototyping that inform the designer at an early stage in the design process.

Designing complex systems and services requires unique forms of prototyping. Students need to be able to envision a future, and produce a low-fidelity representation of that future. This may include acting through scenarios and creating digital or physical artifacts.

Develop the vocabulary to discuss design solutions with other members of a product development team.

Students learn to clearly articulate their design ideas to team members of other disciplines.

Develop the vocabulary to defend the social value of their design solutions.

Students learn to speak the language of value, as pertaining to the social and humanitarian benefits of a solution, and to appropriately frame their solution in the contexts of the problem space and the people they are serving.

Curriculum Structure

The curriculum balances traditional lecture-style knowledge transfer with the creative learning-by-doing, experiential style of the design studio environment. Students rapidly gain knowledge of various humanitarian issues along with advanced design knowledge of synthesis, service and system design, and entrepreneurship. Much of the curriculum is focused on a 32-week thorough investigation into one humanitarian issue. This period permits the students to propose, prototype, analyze, and evaluate multiple iterative design solutions. As students progress through the curriculum, they work collaboratively in a studio environment that supports rapid ideation, informed trial and error, and an immersive process focused on ethnographic user-centered design research and synthesis. Courses are run formally—with syllabi, assignment/project briefs, and ongoing critiques and evaluations—yet studio projects maintain an "incubator" feel, focused on the production of functioning solutions.

The curriculum presents three types of classes—methods, theory, and the application of these methods and theory in a studio environment.

The curriculum is structured to challenge three false assumptions of students typically bring to a new academic program:

First, most students have a dramatically incorrect view of how much work they can accomplish in a certain amount of time. The curriculum appears overwhelming until they learn to work more quickly, efficiently, effectively, and confidently.

Students also bring the assumption that there is a right answer to their work and that the teacher knows it. This curriculum constantly challenges students to find the right course of action or the next step on their own. They are left to apply learned methods as they see fit.

And students typically view work as a finite process; they expect to "end the work" at some point. This curriculum challenges that perception because students leave the program when they have just begun their own companies and social initiatives. But it's important that students feel a sense of closure upon graduation, so this closure needs to be introduced artificially through presentations of milestones; students cannot be led to believe they will "solve" a problem like poverty in 32 weeks.

Course Sequencing: Overview

Course Details

Interaction Design Research and Synthesis

Interaction Design, Society, and the Public

Rapid Ideation and Creative Problem Solving

Service Design

Evaluation of Design Solutions

Theory of Interaction Design & Social Entrepreneurship

Entrepreneurial Practice

Studio: Foundations

Studio: Research & Synthesis

Studio: Ideation & Development

Studio: Pilot

The next part of this book focuses on the methods that are taught in some of these classes.