Thoughts

Emotions in the Workplace

When I was 8, I took a class in wheel-thrown ceramics. On the first day of class, my teacher made a beautiful two-foot-tall vase and sliced it in half, lengthwise. Imagine, a perfect form, ruined on purpose. I was astounded—and jealous. I couldn’t make anything even close to that, and there he was, ruining it on purpose! He said it was to show us how thick it was. Later, I realized it was to show impermanence. He wanted us to learn that when you get good at making things, the things themselves stop being precious.

Much later, as an 18-year-old design student at Carnegie Mellon, I learned another valuable lesson in making. It was my first semester and my first critique of my first assignment: a hand-drawn self-portrait. The results were up on the wall. Mine was awful, far and away the worst thing on display. It was out of proportion and had poor line weight—even poor paper stock. The only things going for it were marks so soft and tentative that no one could really even see it. My face was burning red, and I was sitting as far back in the studio as I could get, trying to make myself as small as possible. Although I already knew the need to make things to find a solution, I was embarrassed that my execution was so removed from my vision.

In both examples, I was struck by the relationship between making things and feelings. When my ceramics teacher cut the vase in half, I felt jealousy and shame. During the critique at school, I again felt shame that because my work wasn’t good, I wasn’t good. For many people, what drives such self-criticism is perceiving the gap between their work and their taste, according to Ira Glass, host of National Public Radio’s This American Life: “All of us who do creative work, we get into it because we have good taste. For the first couple years, you make stuff, and it’s just not that good. But your taste, the thing that got you into the game, is still killer. And your taste is why your work disappoints you.”

That mismatch comes to life in the creation of an artifact. The creative process is, abstractly, about conceiving of things that didn’t yet exist, and then actually making them exist. When I was a creative director, one of my favorite things to hear in the office was, “Well, I made a thing.” It’s often a declaration of achievement, but just as often, you hear a tone of frustration, as in, “Well, I made a thing. But it’s not very good.”

When you make a thing and inject a little bit of your essence and your feelings into it, you’re vulnerable. There you are, showing these feelings to anyone who wanders by, and waiting to hear their reactions. Putting yourself in that vulnerable position requires absolute trust. When junior staff members make something, doing so can open a giant space of introspection. What often fills that space is an emotional churn similar to what I experienced in my clay and drawing classes. The thing they make becomes a placeholder for all sorts of other things: Aspirations. Self-deprecation. Anger.

These emotions are weird things to talk about in a business context. As managers, we’re not therapists. Work is supposed to be professional, and emotion isn’t welcome in the traditional workplace. But it finds its way in, particularly in a high-profile creative setting. The more a company believes in creativity, the more it shines a light on the output. And when that happens, designers realize their limitations. This realization introduces emotion into the workplace in a way that’s no longer hidden.

In a creative organization, emotions run wild. At the same time that the made thing causes the designer’s emotional self-critique, the thing prompting critique from others, exerting additional emotional pressure.

Let’s take a look at emotions in the workplace, and how they often get in the way of driving creative vision.

Understanding emotions in the workplace

Imagine the most conservative environment you can think of—a company or organization that you would never, ever describe as creative. It’s likely that you thought of the U.S. government, which we typically describe as massive, slow moving, and overly bureaucratic.

Embedded in that conservative environment, Stephanie Wade was the Director of the Innovation Lab at the United States Office of Personnel Management (OPM). The lab’s mission is to introduce creativity to various government agencies and the White House. The lab’s goals are to help government employees understand the role of creativity in dealing with large-scale social problems and to help organizations think differently about these problems. Wade and her team built the lab, modeled on an education consultancy, upon three core pillars.

The first pillar was that the group would be subject-matter experts in creativity and design innovation within government. This meant hiring and building a unique skillset—bringing in strategic visual thinkers who would solve problems in unique ways. This pillar was about building a culture of problem framing, critique, and ideation.

The second pillar was to serve as teachers—training government workers to apply a creative approach to solving challenging issues. This pillar was a way of spreading the culture, language, and skills of creativity through government.

The third pillar was to directly take on the wicked problems facing government, and use a creative approach to solve them. One of the lab’s early projects—a litmus test for the pillar—centered around the National School Lunch Program of the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA).

The program provides discounted or free meals to students who are unable to afford lunch on their own through payments to schools.

Internally, the organization knew that the program was plagued by undocumented, inaccurate, misdirected, and misused payments. The program had a 15% error rate, higher than other government programs, including unemployment insurance, Medicaid, Medicare, and rental housing. The lab partnered with USDA’s Food and Nutrition Services to address these improper payments. Instead of performing traditional audits, such as reviewing documents and payment processes, Wade’s team leveraged the design-thinking process to better understand the school-lunch landscape.

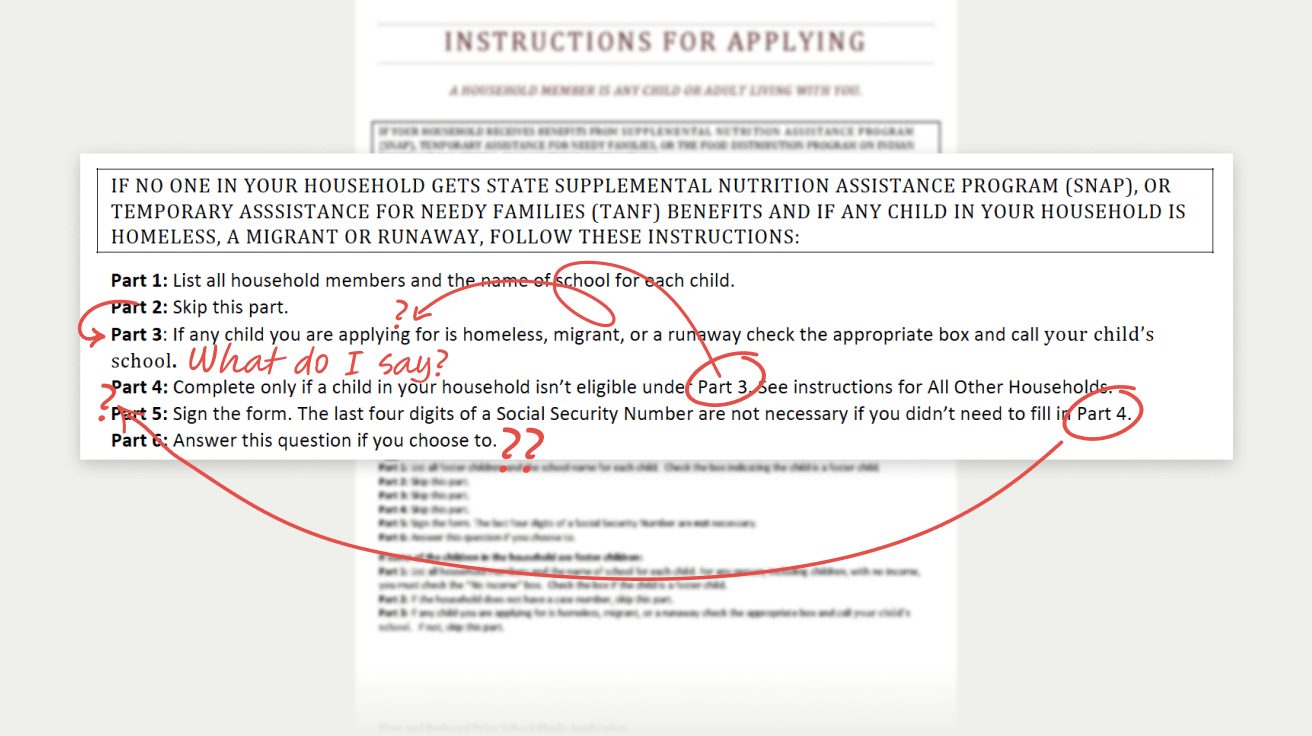

The team conducted qualitative research with the process’ constituents. “We talked to the school-lunch ladies and the principals, and we watched the kids in the program go through the process.” The research revealed one of the biggest problems: the four-page paper application that parents of program recipients must fill out every year. It was a problem because, “…it felt like it was written for someone with a PhD in government. It wasn’t written for the audience, which are low income, and English is most likely not their first language. They have poor reading and writing skills… The application error rate was very high, and to compensate, schools were organizing events at night to help the parents fill out the application correctly.”

The application included instructions similar to a tax form, with compound logical if/then statements:

“IF NO ONE IN YOUR HOUSEHOLD GETS STATE SUPPLEMENTAL NUTRITION ASSISTANCE PROGRAM (SNAP), OR TEMPORARY ASSSISTANCE FOR NEEDY FAMILIES (TANF) BENEFITS AND IF ANY CHILD IN YOUR HOUSEHOLD IS HOMELESS, A MIGRANT OR RUNAWAY, FOLLOW THESE INSTRUCTIONS.”

The application even contained circular references to the form itself (“Part 4: Complete only if a child in your household isn’t eligible under Part 3. See instructions for All Other Households”).

The team linked much of the waste of millions of dollars per year to the fact that parents were inaccurately filling out the form. Then they set to the task of finding a solution—one of the first times a design-thinking approach was leveraged in the government. The challenges in finding the solution, the team found, weren’t about the actual design problem of making the application form easier to understand. They were about the emotional and cultural changes necessary to implement a creative process.

Wade further describes those some of those challenges and how her team addressed them.

Team members were skeptical of a new, creative process.

They were made up of both existing government employees and new hires with a design background. The existing government employees lacked confidence in the creative process—including qualitative research, ideation, and idea generation—because they hadn’t seen it work. They questioned, and often didn’t trust, that their efforts would lead to a success.

This is a common worry because, as we’ve seen, the creative process feels (and often is) fuzzy and subjective. As we’ve also seen, the goal of a creative engagement can be poorly defined, and the process itself generates constraints that, in turn, provide clarity. For team members who had never completed the process, the methodology was difficult to embrace and skepticism was difficult to suspend.

To address this problem, the team’s designers created a training curriculum for other team members at the same time as the team pursued the USDA program work. The workplace became an environment for learning, not just doing. The team also reapplied this set of educational materials to share outside the team.

Team members were unable to see alternative, creative solutions to an existing problem.

Many had been working on the school-lunch program for more than a decade so they were entrenched in their view of the problem. They were experts in improper payments, so they framed the problem based around what they knew rather than in new ways. That’s the expert’s blind spot I mentioned in the previous chapter.

To shift this entrenched perspective, the team focused on quick iterations built on user feedback. The team, Wade explained, “would play around with ideas, and then approach random people on the streets to test them.” By leaving the building, they were able to generate anecdotes about the work and bring evidence of successful progress to drive future iterations. And by building empathy with non-experts during real-world qualitative research, team members could see new problem frames.

The team was skeptical of a new process being introduced into the organization, driven by a new leader.

Wade’s background was in creative consulting, not in government. And, typical of the attitude toward any new leader in an organization, there was fear about how that she would adapt to the culture or attempt to change it.

Wade mitigated this feeling of distrust by participating as a hands-on leader, doing the creative work alongside the team. She developed a “we’re all in this together” demeanor that built a feeling of comradery and trust. This hands-on approach required tradeoffs with her management work. “To manage my workload, I put a line in the sand. I’m doing x hours with my project team, and x on the operations side, and something will get sacrificed. I protected that, so I could be there with the team in a real way.”

The culture of creativity initially established an “us versus them” atmosphere.

The new creative staff was viewed as shiny and new, and it seemed at times that they were leaving behind the people that had been working on the problem for years. To champion creativity, Wade says, the designers “wore that rebel cape on the outside. But that rebel nature alienates us from who we are trying to win over.”

To be inclusive, designers became more aware of their language. “We tried not using the traditional design language I had learned.. I made it colloquial.” Common language made the new approaches more accessible and made new techniques feel familiar and less strange.

The problems Wade experienced and addressed all stem from two cultures colliding. Almost by definition, government is slow. Checks and balances ensure the discussion of controversial ideas and the mitigation of risks. By introducing and embracing creativity, Wade encouraged the team to move fast and take risks. “A creative culture,” she says, “means daring them to come up with crazy ideas.” More than anything else, establishing trust is key to introducing the creative process into a conservative environment like the U.S. government.

Establishing trust is also fundamental for introducing creativity into any other organization. Trust enables team members to depend on one another to do what’s right, and to operate from the same point of mission and toward the best (and shared) interests of the company. Those are often also major goals of team-building retreats and corporate-mission-alignment meetings. Team-building activities are often about showing one’s vulnerability, so that team members can relate to one another on an emotional, human level.

Creative trust focuses on understanding the way to offer and deliver criticism, and how to receive and react to a creative deliverable. When working on the USDA project, Wade identified that the delivery and receipt of criticism required meaningful creative trust. She explains, “when you develop or create something, it feels so great. It can be a new graphic image, a sketch, it feels exhilarating and it’s a part of yourself. And when you put a part of yourself on display at work, to be critiqued in a vulnerable way, it’s sacred. How you handle that artifact, that manifestation of creativity. It is really important to treat that in a way that’s respectful and values the team’s work, their creativity.”

Many of our traditional and conservative organizations have cultures similar to those of the government. Those cultures don’t include making or critiquing, so employees don’t understand how to react to the artifacts. And that lack of understanding can cause introversion: “In that type of environment, I know that when I put it out there, they don’t know how to handle it with kid gloves. It makes me not trust them to handle it the way I want… I don’t trust them to critique it.” Wade isn’t saying here that she worries about receiving a negative critique. She’s saying that she worries about receiving a wrong, or inappropriate critique, such as “I don’t like it” or “That will never work.”

And so, in addition to training the team and the entire organization in design, Wade also had to train them in how to react to creative deliverables. Critique, in this context, means to identify something good to build towards new ideas. Her technique is to “start with the good.” But, she said, that’s not what she learned in grad school. “…I was taught to find the weakness because it meant I was smarter. Focusing on the good is never wrong, and it’s never insincere. There’s always some point of magical goodness in something, some element of beauty, of hitting the mark. Focus on that, and figure out how to build on that to focus on the next iteration.”

Over time, Wade and her team were able to establish a culture of trust that brought together disparate perspectives to function effectively. Her teams were able to embrace criticism as a fundamental part of the creative process and to shepherd ideas through a creative engine with ease. Their empathetic journey into the school-lunch program included working with users and proposing ideas that seemed outlandish or unrealistic. It resulted in a redesigned application of a single page.

According to USDA’s Jeff Greenfield, the office responsible for the program “…has credited the lab and its design process with changing how we approach problem solving. “ The success of the program, and the lessons learned, have shifted the entire way this government organization approaches creativity.

Takeaway: Train the organization not just in the method of critique, but also in the culture of creativity and the need for trust.