Thoughts

Sell It With Pictures

Think about your home.

Walk through it in your head and imagine how a visitor sees it—but don't clean up. What does this guest see? Artwork, children's toys, computers, televisions, books, dishes? Is it messy or organized? Think about how someone might interpret the clues of your life.

Using this exercise in my home, I see a kitchen that's the centerpiece and imagine people entertaining in that room. It looks like they find comfort in domesticity and creativity around food. I would describe the modern kitchen and talk about reading a lot of books and not owning a television.

In ethnographic research or design research, it’s important to understand both what our participants say and the context in which they say it. A home is full of details that allow us to see both their aspirations and their realities.

Looking a little closer, there are dishes in the sink and some paint chipped on the lower cabinets. There are cat food dishes, a stack of mail, and half a baguette that may be a few days old.

Overall, the theme in my home is it’s a beautiful place of comfort that my wife and I are deeply proud of, but with signs of being just slightly ignored. We clean regularly but haphazardly and there is always paperwork we haven’t gotten to yet. There’s no television but we have a few iPads and computers. We eat healthy food, but I drink plenty of beer.

Home is an interesting mix of aspiration and reality. We surround ourselves with items we feel represent us to other people as well as things that make us feel comfortable.

Scenes from Research

Recently, we worked on design strategy for a company developing new ways for customers to keep their homes clean.

First, consider our participant Martha.

"I like junk. I should have a bumper sticker, 'I stop for garage sales.' Every once in a while you read things like 'somebody found an original map of Galileo, in the Goodwill... $6.5 million.' Just the little dreaming, kind of like 'well, you never know.' It's an adventure. A treasure hunt."

Martha’s home in North Dakota is decorated with some of her best finds, and she's built a business around “the hunt”—turning old furniture into what she described as "rustic shabby" pieces resold with a markup.

Some of her self-declared compulsive buying stems from her mom, who grew up during the Depression. "It's like you don't throw away a T-shirt or old socks or things like that, that's what you dust with or that's what you wipe with, or you make rag rugs. Every bit of material gets reused in some way... the Depression, living on a farm... That's the way she grew up and lived, so it wasn't anything new to her. So I grew up that way."

Martha speaks of her work with pride and a touch of self-deprecation. "Germs can be good, you need to build up your immunity. Or maybe I'm just rationalizing because I'm a lousy housekeeper. And I think part of it too is that we have so many projects going on, and we have dogs, that I've just got to lower my expectations... I mean I'd love to have this stuff out of sight. It's unsightly.”

Martha starts coming to life when you hear her story and imagine how her home and projects look. Now, consider Martha's story again with the added the context of photographs from her home.

Presenting Martha's story in words sparks listeners’ imaginations through narrative. However, when I'm presenting a design strategy, grounded in research with people like Martha, I want to build a persuasive argument so as to see her story through a specific emotional and mental filter. Looking closely at the pictures, without judgement, gives Martha depth and a more complete voice.

In another project, I spoke with Donny about what it's like to be under or unemployed and how to translate his military experience as a veteran of the Iraq war into civilian-relevant skills.

“I was like 19, I think…but I didn't have a driver's license because my parents wouldn't pay for it. I didn't have the money and I got in this high-speed chase…and then I'm like I'm not pulling over. I'm gonna get in trouble and I shouldn't be driving their car. Yeah crashed and that kind of started everything…Parents said get out. They kicked me out and I had to find something. That was the army. That was the biggest thing that really straightened me out.

"It was a rude awakening for me. I mean, I remember going there and this recruiter says it is kind of like college life and won't be that bad. But we get right off the plane and I've got guys screaming at me in the face. And we're hearing, ‘Oh, we're starting basic training, and you lose all your freedom. You can't do whatever you want."

"After the basic training, you start job school and I thought that was a little bit easier transition as there you are a little more independent. You kind of, you still gotta show up to your class and do your job school but then…on the weekends you can go away and do what you want, within reason, obviously."

Donny's words create a mental image that, like Martha’s, may or may not be accurate. In order for you to experience something close to what I saw, heard, and felt when I spent time with Donny, it’s helpful to show real scenes from his house. These aren’t “killer images” that drive home a fundamental point, and that’s precisely why I include them: this type of context brings Donny to life so that he’s real and relatable.

Donny becomes much more human when you see images from his life.

The Power of Imagery

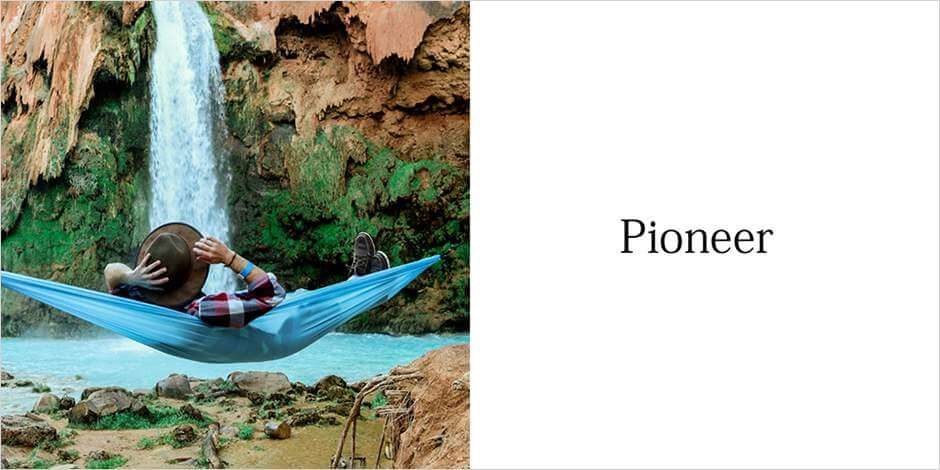

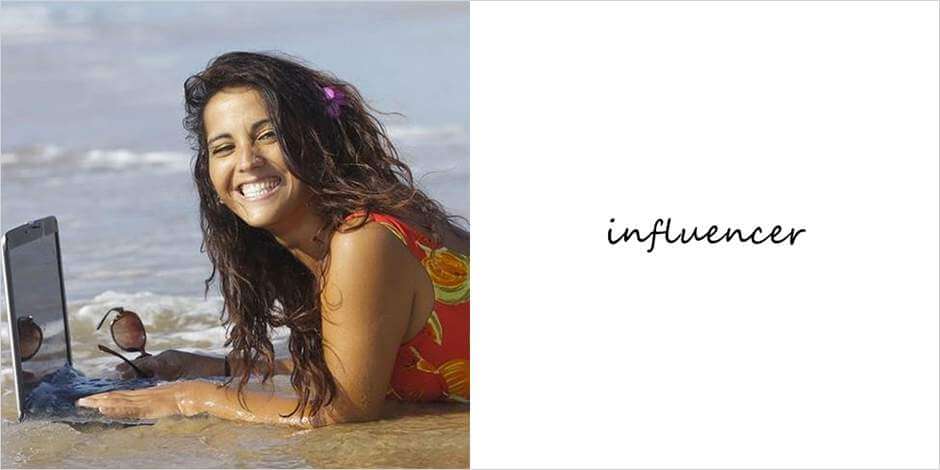

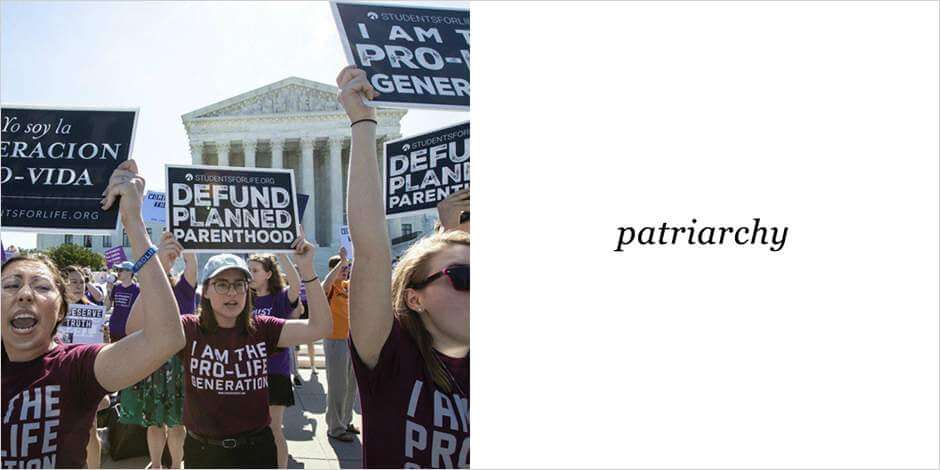

When I was an undergraduate studying design at Carnegie Mellon, one of the foundational exercises we were assigned was something called Image/Word which includes placing a square image next to a single word, using the juxtaposition to create a new meaning.

The team at Narrative had fun with this as well. Here are mine, Matt's, and Chad's.

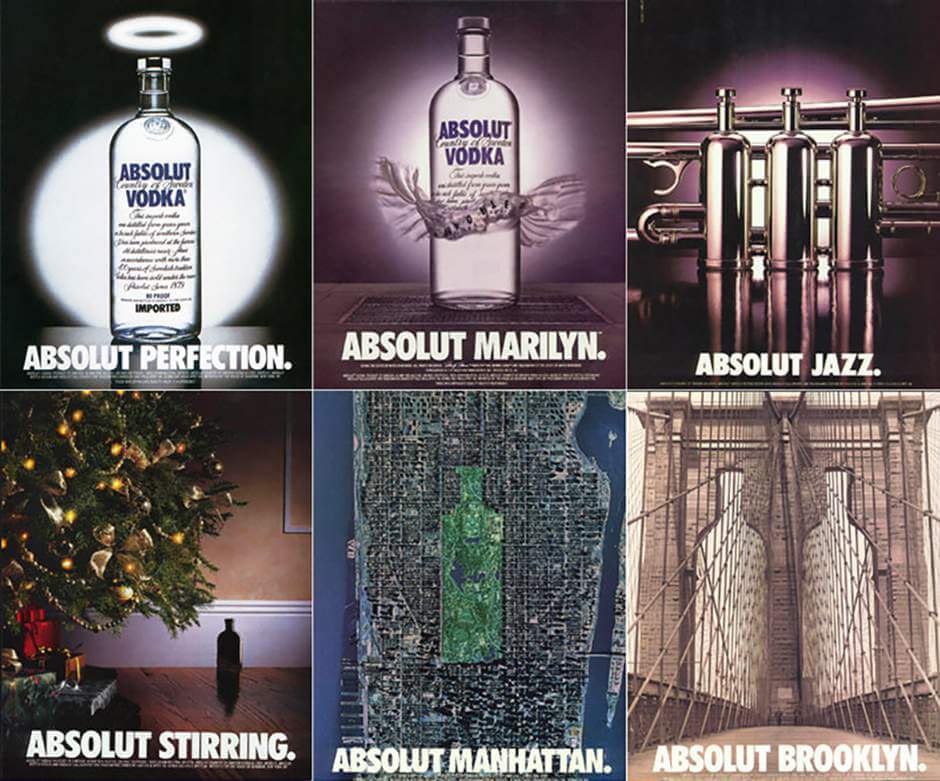

Visual designers have long understood the persuasive relationship of imagery and words—think of the Absolut Vodka ads from the ’90s:

Persuasion

The editorialization that happens in ads and comics is similar to what we do when including imagery from the field with quotes and transcriptions from our participants. The importance of this contextual field research when developing a design strategy is second only to forming a deep and meaningful connection with the participant themselves. Immersion in their space, and the subsequent synthesis of that immersion, helps us formulate the information my client needs to know and provides images to substantiate our perspective and direction.

Qualitative field research is hard and time consuming—remote interviews or quantitative surveys would be much easier—but for the increased authorship that comes from conducting in-home research. The context of someone’s home provides effective tools to shape and build a persuasive argument and the image/word relationship paints your participants and your strategic agenda with an equally rich brush.