Thoughts

chatGPT: Technology Is Always Hype And Consumers Don't Care

Technology is a cultural experience. It unfolds over time. It needs duration to become meaningful: designers need time to shape technology so that it feels familiar, and people need time to absorb it into their lives in a way that makes sense to them.

But the inventions we see changing the world always seem to be happening Right Now, and Only Right Now. Designers (and technologists, product managers, and everyone else involved in bringing new products and services to the world) bunch and swarm on the rawness of the invention and defer and delay—or completely lose—the ability to bring its value to the world. And we've got a pretty poor track record of taking our time.

In the late 90s, eCommerce was a "thing." Social networking hit us big with MySpace in 2003. We did the iPhone and 3G in 2007, Bitcoin and blockchain in 2009, and it was all about quantified self in the late 2000s. We learned all about the benefits of being social, local and mobile in 2013; then everything was a non-fungible token in 2021.

Every one of these technologies ended up having real, material value. And each of these technologies, apps, devices and philosophies seem to come out of nowhere. But in retrospect, every one of them had a slow roll of progressive, incremental innovation and invention. On the way to MySpace, early adopters (often made up of teenagers and techies) explored teen party lines, BBSs, Prodigy, America Online, Six Degrees, Friendster, Orkut, and Tribe. MySpace itself was just a dot on the way to Facebook.

And all of these technology changes began in a long, slow grind of academic research and knowledge production, often starting with entirely theoretical observations.

These technologies bring with them a promise of "overwhelming changes like nothing we've seen before." And while they all are like nothing we've seen before, change seems overwhelming only without seeing the historical (and very normal) context and evolution of creation and adoption. Technology introduction cycles have accelerated, given our ability to distribute technologies via technologies, but those cycles are still very, very slow.

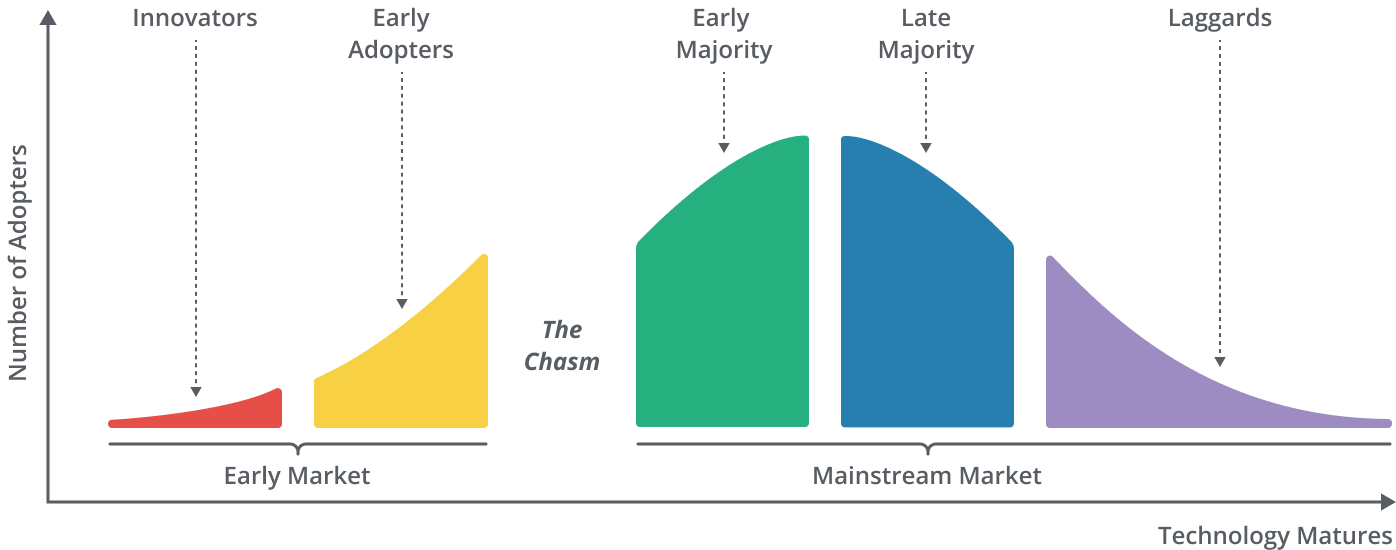

The cycles seem to follow an adoption process like Geoffrey Moore's innovation curve and chasm model:

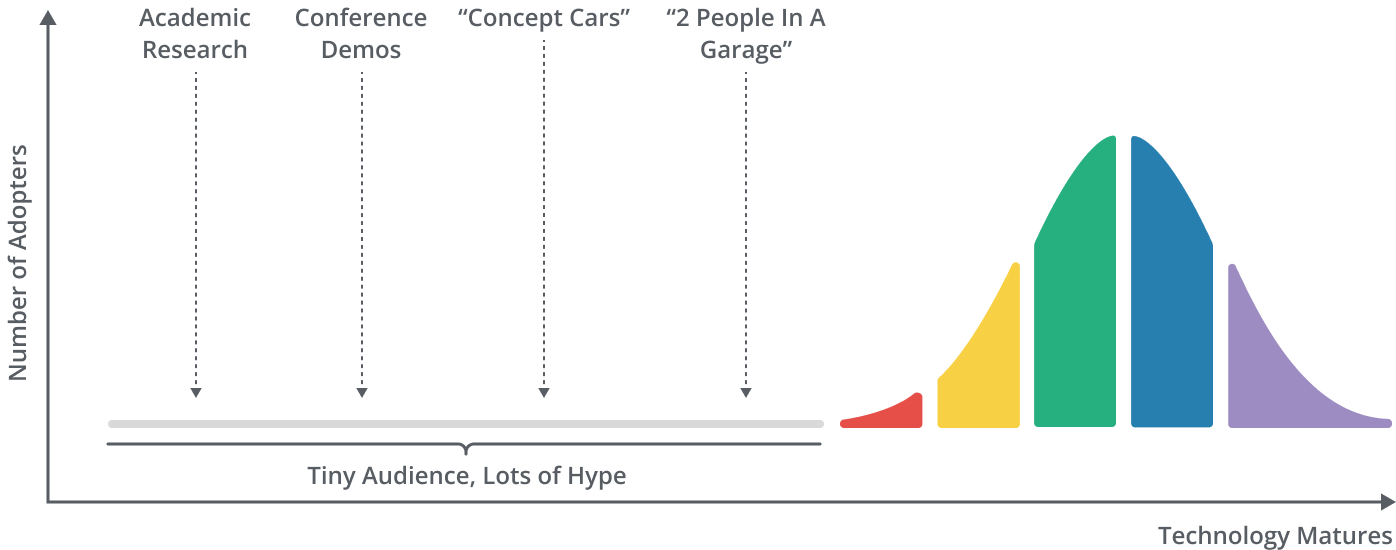

But there's actually a lot more to it:

- New theories are presented in academic research papers, discussing how things might be

- New practices are shown in universities and research labs, showing how things might feel

- New products are envisioned at tradeshows and in the online press, presenting technologies that we may want to buy and use

- Tinkerers start showing prototypes

And it looks something like this:

And it's easy for those of us who make new products and services to forget just how long the laggard tail is. Consider:

In 2009, all television stations switched to digital; 1.7M americans still did not have access to digital-ready televisions. (Source)

In 2019, 42.8% of US households still had landline phones (Source)—that's almost 100 million land lines.

In 2019, 2 million Americans still use dial-up internet. (Source)

We've all sat at the airport and pondered the use of dot matrix printers at the gates; Boeing still uses 3.5" floppy disks in its 747, and Airbus uses them in the A320. (Source)

The list goes on:

VHS tapes were generally considered obsolete in the early 2000s, but some people still use them for recording and watching movies. In 2020, 15% of US adults still own and use VHS tapes. (Source)

Fax machines have thought to be outdated since the rise of digital communication methods, but a huge amount of businesses and individuals still rely on them. In 2017, 82% of businesses still use fax machines. (Source)

An estimated 700,000 typewriters were sold worldwide in 2016. (Source)

In 2018, an estimated 34% of US households still owned a CRT television. (Source)

Old technology tends to hang around, because it's better, or because people don't see the value of its replacement, or because they just don't care to make a change. Technology isn't a moment in time. It's a part of an always-evolving story, with most of the story one that we've already read but only started to understand. Put another way, the exciting piece of technology of this moment has been kicking around for a long time. There's nothing particularly exciting about the technology itself; it gets exciting when we start to look at what it can do for us, and that's something that takes culture and society a long time to get their arms around.

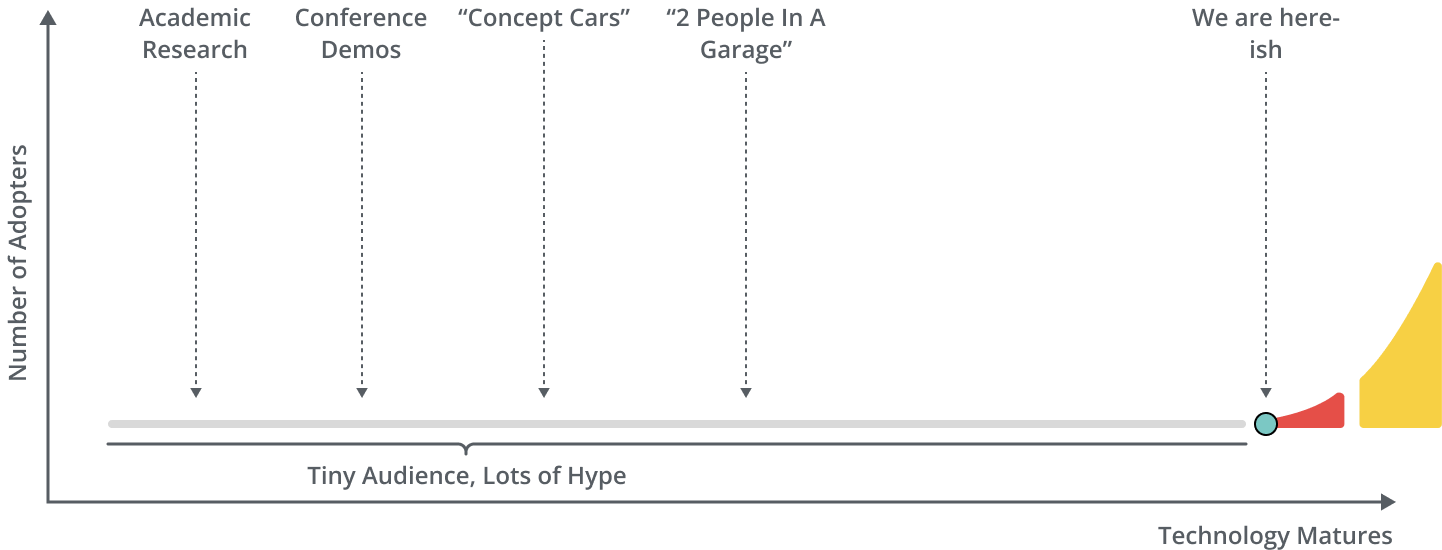

Right now, we're all romanticizing the Moment Of Time Of ChatGpt. But machine-learning driven AI didn't just pop up out of nowhere, and it's not ready for consumerization yet.

Consider these excerpts from the article A Very Short History Of Artificial Intelligence (AI), in Forbes:

1950 | Claude Shannon's “Programming a Computer for Playing Chess” is the first published article on developing a chess-playing computer program. |

1965 | Herbert Simon predicts that "machines will be capable, within twenty years, of doing any work a man can do." |

1968 | The film 2001: Space Odyssey is released, featuring Hal, a sentient computer. |

1988 | Rollo Carpenter develops the chat-bot Jabberwacky to "simulate natural human chat in an interesting, entertaining and humorous manner." It is an early attempt at creating artificial intelligence through human interaction. |

1997 | Deep Blue becomes the first computer chess-playing program to beat a reigning world chess champion. |

2004 | The first DARPA Grand Challenge, a prize competition for autonomous vehicles, is held in the Mojave Desert. None of the autonomous vehicles finished the 150-mile route. |

2011 | Watson, a natural language question answering computer, competes on Jeopardy! and defeats two former champions. |

That's a cherry-picked single milestone per decade; there are hundreds more.

This isn't just a history lesson. It's a simple but important point about technology hype, and cultural readiness. Simple, we're in the tail end of the creation phase of chatGPT, not the adoption phase: arguably, we've barely even started that part yet. Imagine Moore's adoption cycle. We're barely on the left.

This also isn't a “we ain't seen nothing yet” commentary, although we really haven't (imagine the shift from Nokia brick phone to Apple iPhone as an example of a giant jump in consumer-readiness.)

Instead, it's a reminder of a fundamental of design and usability: the user is not like me, and generally, people don't care about technology at all. When designers start to contemplate chatGPT, and all we read about on LinkedIn is chatGPT, and all we see are people trumpeting the value of chatGPT, we need to force ourselves to forget that it's a magical new piece of technology, and instead, focus on the basics. Who is it for? Why do they want it? Do they want it? What will it help them do? Do they need that help?

Technological revolution comes not from new features and functions, but from ways new capabilities help people live, love, play and work. While technology begets technology, the acceptance of a technical revolution is slow, steady, and often. Designers should be good at humanizing technology, and making the strange relatable. We communicate our futures not through code, but through narrative. The best way we can respond to the hype of chatGPT is to skip the tech, tell a great story, and above all, move slowly.

Takeaway: Ignore the hype and focus on what designers do best: help people through creativity.