Thoughts

The Future Has Already Been Determined

It's true: we can predict the future. The clues are there, if we're willing to dig a little. They are tucked away in the confines of academia, often presented in research journals and conference papers.

The Association for Computing Machinery holds annual conferences of technology researchers from all fields. The conferences present academic research, innovations, and experimental findings, and all of the papers presented at the conference are housed in a searchable digital library (unfortunately behind a paywall). And the proceedings from each conference have historically offered a fairly prescient view into things to come. For example, a 2005 article "High speed obstacle avoidance using monocular vision and reinforcement learning" starts pointing at mature technology to identify roadblocks for an autonomous vehicle. Another 2005 article, "Towards an approach for knowledge-based road detection," explores a similar topic.

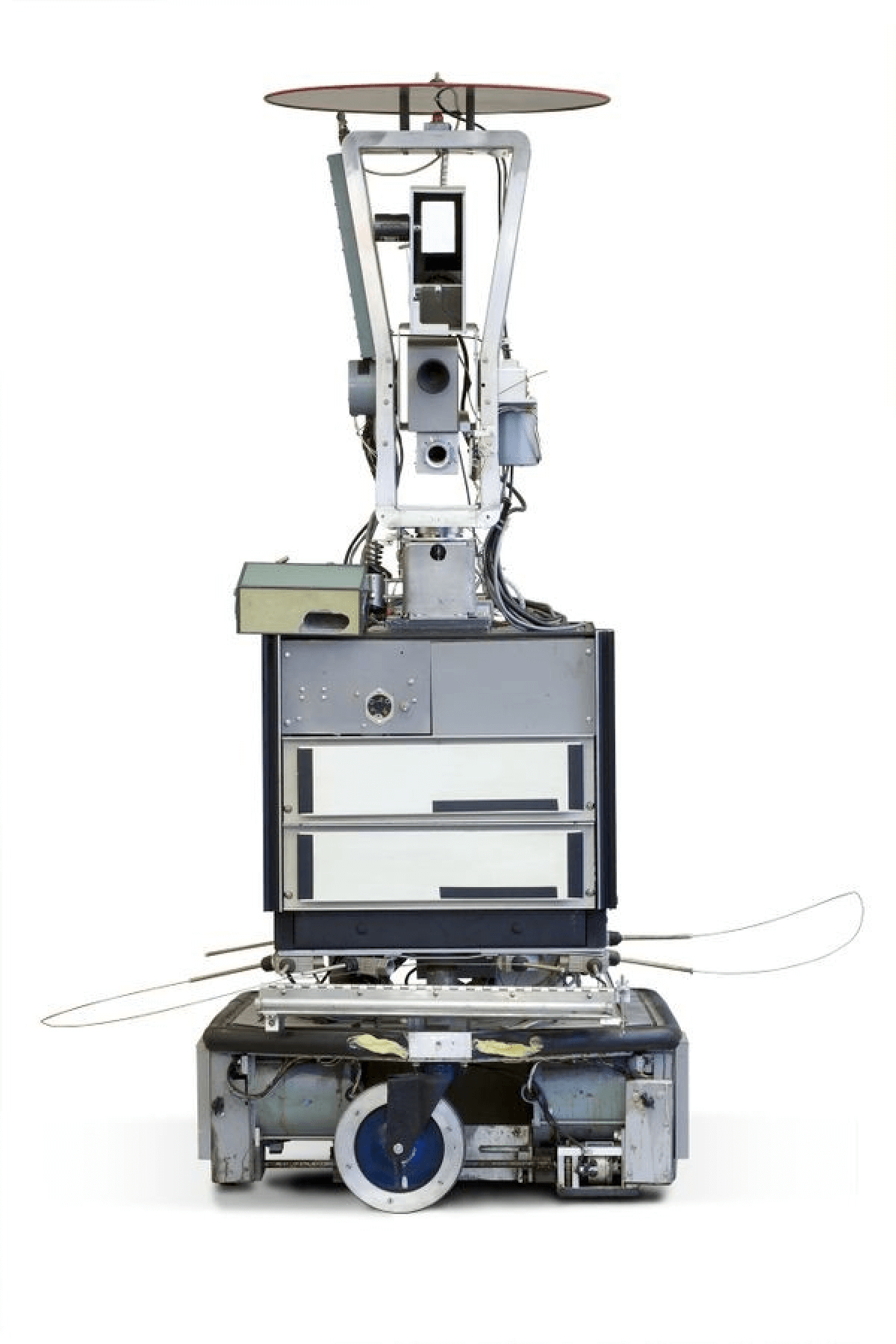

Academic research labs also publish their work, and the Stanford Research Institute has been publishing work since its inception in the early 1970s. In April, 1984, they presented Shakey the Robot (pdf) describing 5 years of research related to autonomous robot navigation. DARPA's Grand Challenge—a competition for self-driving vehicles—has been going on since 2005. Schools like Carnegie Mellon have been exploring automated driving solutions since the 90s.

These are practical signals along a 30 year path towards autonomous vehicles. Microsoft researcher Bill Buxton describes that it takes approximately 20 years to move from an idea to a mature "billion dollar industry." In this case, he's off by a decade, but the point stands: there are gestures to what the future will look like, hidden in plain sight. We just need to learn to read between the thick academic language and style, and view the work through a lens of "consumerism"—of simplifying the technology to the point where it can fit into our behavioral norms and cultural expectations.

For example, the 2018 conference of "Human Factors in Computing Systems" (CHI) included content like this:

- The Making of Performativity in Designing with Smart Material Composites: "the making process of electroluminescent materials in which matter, structure, form, and computation are manipulated to deliberately disrupt the affordance of the material."

- Point-and-Shake: Selecting from Levitating Object Displays: "acoustic levitation enables a radical new type of human-computer interface composed of small levitating objects."

- Multi-Touch Skin: A Thin and Flexible Multi-Touch Sensor for On-Skin Input: "We present the first skin overlay that can capture high-resolution multi-touch input."

- Metamaterial Textures: "We present metamaterial textures—3D printed surface geometries that can perform a controlled transition between two or more textures."

I don't have to have a crystal ball to see that we're a decade or two away from a revolution of materials, where the divide between physical atoms and digital pixels has closed. We'll probably witness the same funding swarm around these technologies that we're currently experiencing around AR, VR, and machine learning. And, we'll see these technologies find their ways into really dumb consumer products, too.

There's another track of research that runs in parallel to the research on emergent technology: investigations into how people respond to these new technologies and how culture adapts to new technology-driven behavior. While the technology research dumps raw material into the innovation engine of corporate product and service development, this form of research almost acts a cultural check on the negative bullwhip of these innovations. The research findings live in the same conferences, journals, and seminars as the technology research; consider these from the same 2018 CHI conference:

- Accountability in the Blue-Collar Data-Driven Workplace: "This paper examines how mobile technology impacts employee accountability in the blue-collar data-driven workplace."

- The Unexpected Entry and Exodus of Women in Computing and HCI in India: "Indian familial norms play a significant role in pressuring young women into computing as a field."

- 'A Stalker's Paradise': How Intimate Partner Abusers Exploit Technology: "This paper describes a qualitative study with 89 participants that details how abusers in intimate partner violence (IPV) contexts exploit technologies to intimidate, threaten, monitor, impersonate, harass, or otherwise harm their victims."

There's a clear pattern. Technology researchers, drive by curiosity, extend the limits of our technical capabilities. After several decades of refinement, startups and corporations get their hands on these new capabilities and the raw material of innovation, and slowly nerf them into products suitable for people to buy and use. And then the academic researchers come in to observe the mess we've made of ourselves.

Design strategy finds itself right in the middle: presenting a vision of the future for how to commercialize those raw technical advancements. Often, these visions are displayed as overly-perfect and overly-valuable. An automated fridge knows when you are going to run out of milk and automatically buys the milk for you while you are at work. An algorithm predicted that, since your connected scale is showing you are a little pudgy around the edges and we've seen this behavior before in people just like you, there's a statistically significant likelihood of you going on a diet pretty soon—so the store automatically substituted 2% milk without your asking. The milk is automatically paid for, and since the store is tracking the location of your self-driving car on the way home, a drone delivers the milk to you right as you glide up to your house.

It's a totally unplausable vision of the future, and more importantly, it's a not-very-good one because it ignores all of the things that make life real: running into an old friend, struggling to find a parking spot, impulse buying ice cream and skipping the diet, and so-on. It's sort of the Soylent of an experience. Rob Rhinehart, one of the founders of Soylent, described that their meal-in-a-bottle product idea emerged because "Food was such a large burden... It was also the time and the hassle." But life isn't something to optimize, it's something to experience, and these perfect visions of technical adoption ignore this.

We can tell the future by burrowing into those academic journals. It's tempting to burrow only into the ones showing the brilliance of new technology, and then to imagine how that brilliance will shape an idealized world. But as a design strategist, our task isn't just to paint a picture of a perfect world. As we backtrack through the 20 year trail of evidence, we can simultaneously look forward to predict the cultural acceptance or fallout from the things we are proposing. In this parallel track, we can start to prescribe visions of the future that proactively anticipate and "solve" some of the cultural problems we're likely to create. We see these problems now most noticeably with Facebook, privacy, and data-ownership, problems that could have been proactively addressed while the platform was emerging, rather than only now in retrospect.

We're collectively enamored with new technology, and we gravitate towards futures that echo science fiction. A video of acoustic levitation is pretty bad-ass, and most people would probably rather watch that than learn about accountability in the blue-collar data-driven workplace. But that's a problem—the second is far more important for practicing strategists. When we start to predict the future, which, it turns out, is fairly easy to predict, it's tempting to look only to the technology.

But we're not only responsible for knowing when technology is going to tip. We're also responsible for understanding the right way to manage that tip, for managing how it impacts and shapes culture. If we're only tracking the tech journals, tech articles, and tech conferences, we're missing out on the clues about how technology should be presented to people. These clues tell us how to wrap technology in behavior that's plausible, and how to predict the social fallout that's inevitable with large scale behavior change."