The power of storytelling to shape and drive product roadmaps

The Power of Stories

If we were to tell you that once, during research, Matt, our VP of Design, tagged along while a convicted felon who’d been jailed for murder sold drugs, would you be surprised?

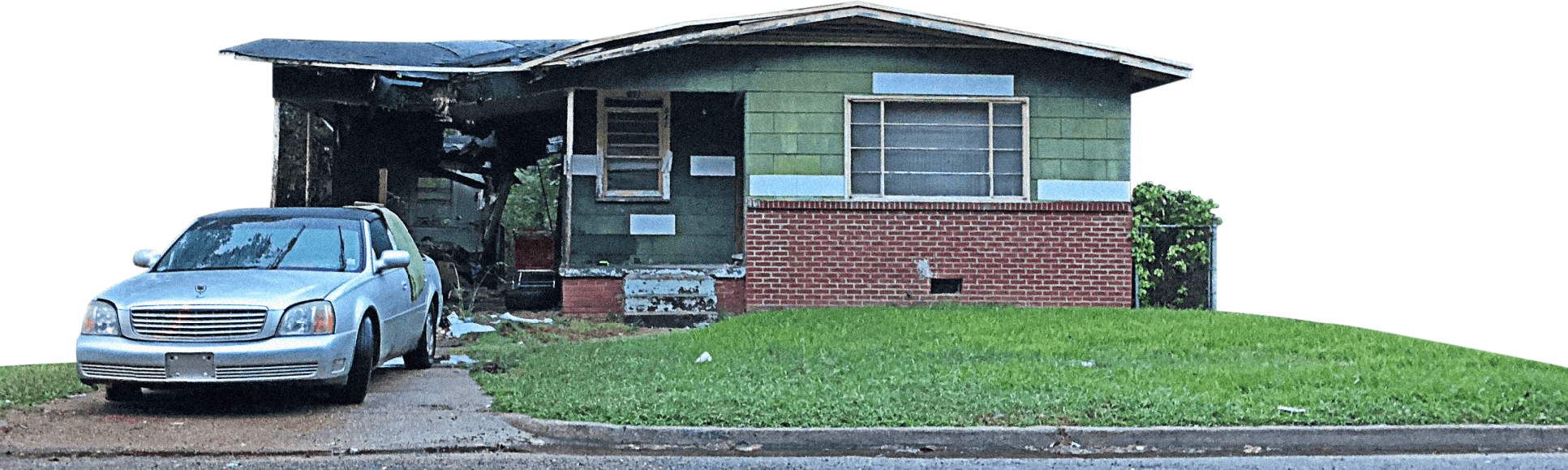

It wasn’t what Matt was expecting either, but it happened. We were conducting research for a politician into people living in poor socio-economic conditions. As part of this, Matt and our client James—an urbane, conservative politician’s aide—visited a poverty-stricken area of the city to meet some people there. For both men it was as far removed from their normal experience as it was possible to be.

The first participant Matt and James met with was Raymond, a tall, thin man who was rubbing his eyes like he just woke up (because he had). “Hey Raymond,” said Matt. “We’d like to watch you while you work.”

“OK then ...Let’s go deal some drugs!”

Raymond skeptically eyed both Matt and the be-suited James. “Watch me work ... I deal.” He finished the sentence, sensing that we didn’t really get it “... drugs. You know, crack. Meth.” Matt rolled with it. “OK ... then let’s go deal some drugs!”

Raymond led Matt and James to a different world—one with graffiti covering the buildings, broken glass on the sidewalks, and a general sense of disrepair. Two or three young men with hoods pulled low over their heads lounged against a wall, staring at the men as they passed by. When Matt started to worry about the safety of the expensive camera equipment he was carrying to record the research, Raymond reassured him.

“You’ll be fine,” he said. “I got you.” He showed a handgun pushed down the side of his jeans.

Raymond was thirsty, so they stopped at a gas station and bought some beer (never mind that it was 9:00 in the morning).

Then, as they made their way to the stash houses where he stored and sold his drugs, Raymond reflected on the changing nature of the neighborhood. Gesturing to an adjacent area in which a Whole Foods had just opened, he described how gentrification was taking over, and how the men in his community struggled to find work. “They wanna work, though. They wanna apply themselves. But they got a record—they no longer needed.”

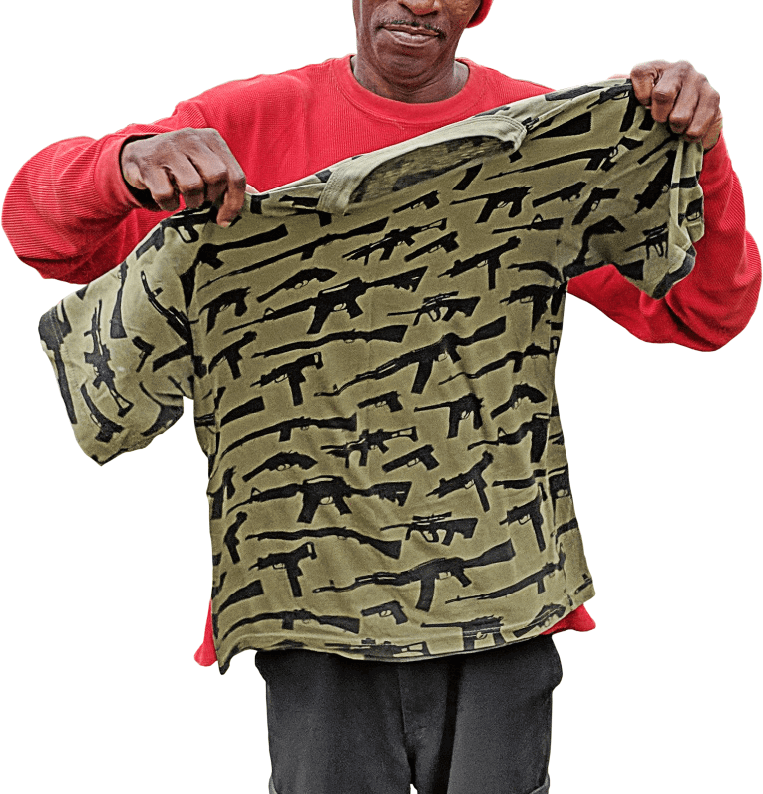

He himself had encountered parts of that system, he said, when he was in jail for many years for a triple homicide. While incarcerated, he’d learned the art of screen printing, so now his plan was to transition away from selling drugs to become a screen printer. He knew what he was going to create, too. He’d already started printing shirts with pictures of guns on them, just like the one he was wearing that day.

Matt was impressed and asked if he could have one for himself; Raymond said yes. And that’s how Matt, our VP of Design, became the proud possessor of a green shirt with black weapons all over it, created by an ex-felon drug dealer who was on his way to becoming a screen printer. You couldn’t make it up (and we haven’t).

While we were telling you this story, we’d bet that you become a little engrossed in it.

Did you worry about what would happen to Matt and James in that dangerous place?

Did you wonder if Matt learned anything from the experience?

Did you imagine him putting on the shirt and showing it to his wife that night?

Did you smile at the thought?

Stories transport you and make you see the world through someone else’s eyes. In this case, you were also prompted to see things from Raymond the drug-dealer’s perspective.

We imagine that his life is nothing like yours (it certainly isn’t like ours), but for just a couple of minutes you were in it with him, and with Matt and James. You can’t yet see the implications of the story, but you’ve had the opportunity to give it space by entering a world that you wouldn’t normally live in. It’s affected you (and Matt, and James) in a way that a set of facts about drug crime, or statistics about the lives of ex-felons, could never do.

Why stories are important

We once carried out some research with a photography student, Becca. As we approached her house we saw a man, shirtless, letting his dog poop on his neighbor’s lawn. He waved at us and—without cleaning up after his dog—went inside to summon his daughter.

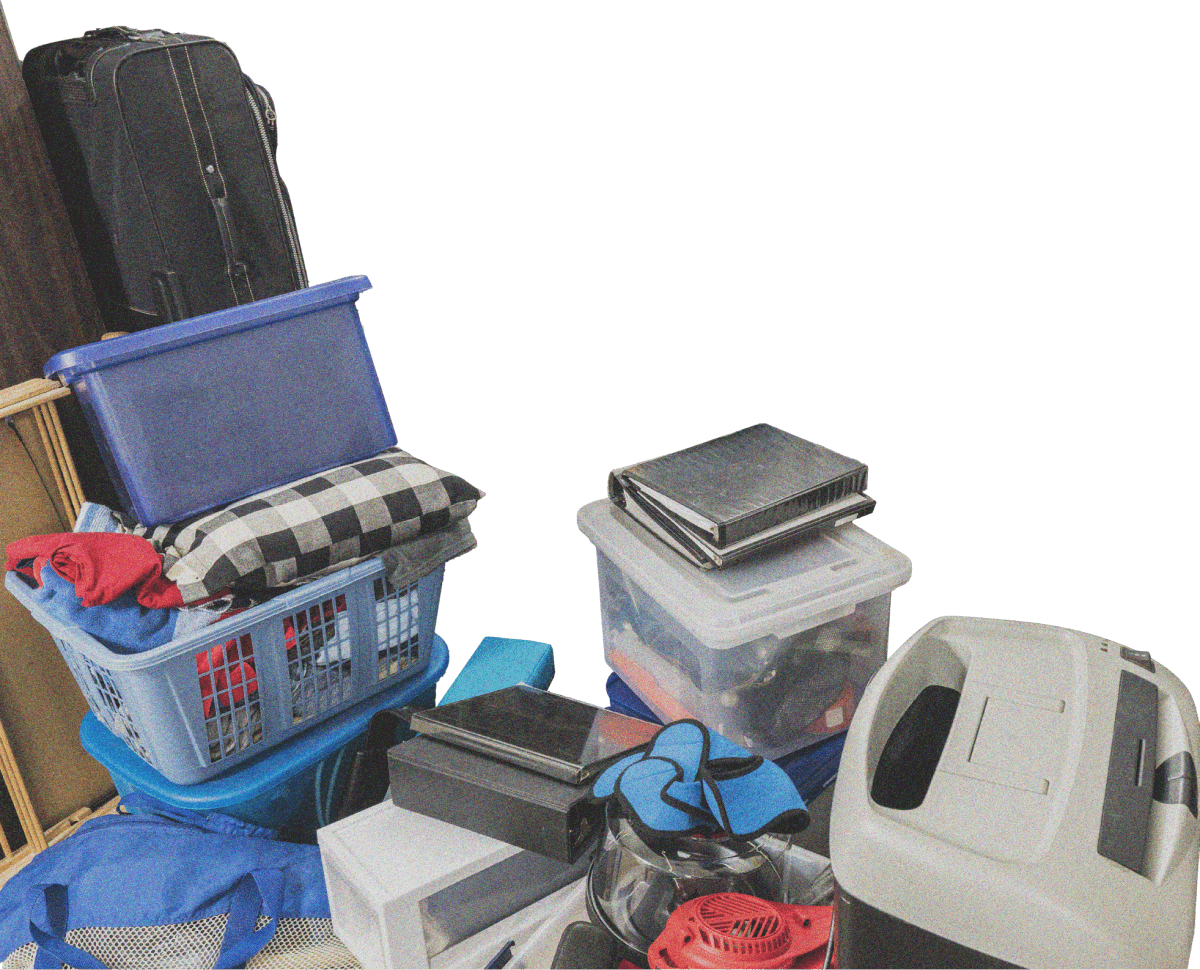

The garage door opened and we could see boxes and boxes of stuff towering all the way to the ceiling.

Becca, a smiling 23-year-old, appeared, squeezing herself down a thin aisle. She asked us to wait a moment, went back inside, and returned several minutes later. Once we were invited in, we had to thread our way between boxes and various belongings which crowded most of the house. A tiny area was cleared on the couch—an obvious attempt to provide us with a clean place to sit.

As we talked to her, Becca revealed that she was finally within reach of graduating with a photo degree, but was thinking of dropping out. The reason? She couldn’t afford the final $3,000 that it would take for her to complete it. The cause of this was heartbreaking. Her dog-walking father was a hoarder and had spent most of his family’s money on the items that cluttered their home. On top of that, he’d incorrectly filled out the financial aid documentation for her course and had hidden his mistakes until it was too late to correct them. She didn’t blame him—she clearly loved her dad—but without that final $3,000 she was on the brink of wasting years of work and ending up without a degree.

After the session we got into our car to drive back to the airport, and started talking about Becca’s personal story; we were so affected by it that we briefly discussed mailing her an anonymous gift of the money. For a variety of reasons around research ethics we didn’t, but we really, really wanted to.

This experience gets to the heart of why stories are important: they transport us into a new context. They lead us to temporarily abandon our rational, logical minds so that we can inhabit an emotional space in which we believe in something different from before, and thereby allow us to enter an alternative reality. Through this, stories give us opportunities to believe in the experiences of others. They also stimulate our curiosity, which prompts us to ask questions.

Take a look at these two more—again, real—examples, so you can see what we mean.

It’s 10:00 am on a Wednesday morning at Los Angeles International Airport.

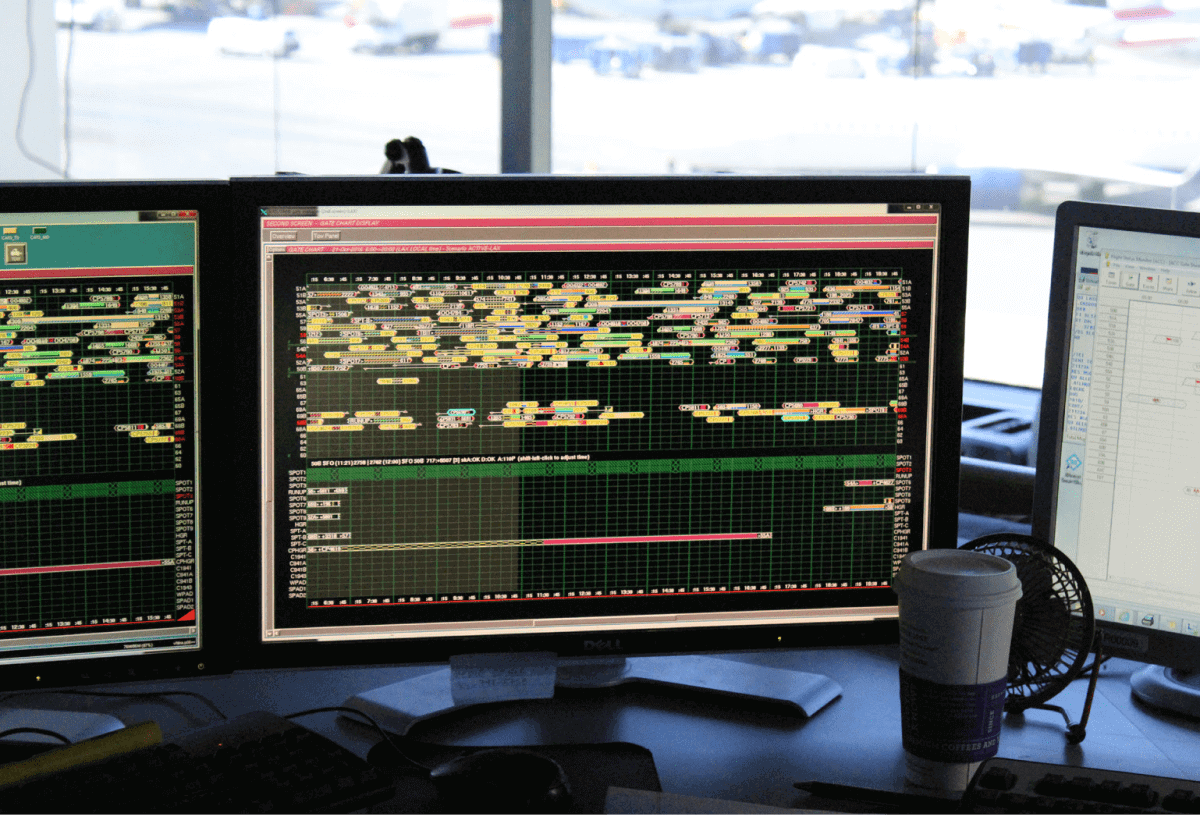

The rain is pelting down outside but Matt’s warm and dry, deep in the bowels of the building. He’s watching Judith, a station control manager with a forthright manner, an impressive command of airport jargon, and in clear command of her three computer monitors, a hand-held radio, and two phones.

She picks up her radio. “Any available ramp supervisor?” she says. “I need a ramp supervisor down to the dungeon for some HazMat. Flight 1462 cannot go, the item cannot go.”

Judith swivels her chair to face Matt. In a matter-of-fact voice, she says, “So, TSA called us and said there was a chainsaw, and obviously it can’t go on the plane, so I asked for the passenger and flight number. They’ll call the gate in a minute and tell the passenger they can’t board.”

Next she’s on the phone with someone else. “TSA called and said 1462 has a chainsaw and they’re going to collect it ...

Yeah, she checked in a chainsaw ...

I don’t want to know what that’s about.”

Fast forward to the following month and Jon’s 1,000 miles away in Denver, talking with Michelle. She’s a 78-year-old retired teacher and is talking about her financial habits.

“When I first went to the bank,” she explains, “I didn’t know the difference between a savings and a checking account. When I was growing up, we put money under a mattress. If you wanted something, like a car, you took the money down to the lot and bought the car. I still do that, sometimes.”

What made the passenger think it was okay to check a chainsaw onto a flight?

How will Michelle operate in a world that doesn’t work with money under the mattress anymore?

And why had she never learned the difference between checking and savings accounts?

Because we’re drawn in, we can’t help asking ourselves about the wider implications of these stories.

If you were in charge of the TSA (Transport Security Administration), would Judith’s experience prompt you to reconsider your messaging about what people can bring onto planes? If passengers really think they’re allowed to check in a chainsaw, what other safety rules are they unaware of? And if you’re a product manager in a bank, would Michelle’s perspective on banking play a role in not only how you design the screens of your online tools, but also how you build, name, and structure the products you offer? If your customers don’t understand what a checking account is, how can you expect them to buy something more complicated, such as an annuity or insurance?

Stories are more fundamental to our lives than perhaps we realize. When we’re in the middle of hearing a story we’re in a state of possibility, we’re open to new ways of thinking. This is important, because to effect any kind of transformation we have to want to make the leap between the way things are now and the way they could be in the future. What’s more, they help us to feel emotionally engaged with a problem, because facts and figures can only tell us so much and they rarely tug on our heart strings. That’s why we tell stories every day—to convince ourselves of something, to make a point to someone else, and to imagine new things to come. And it’s also why, as design strategists, we base our research methods on the gathering and telling of stories. Unlike fiction, our stories are based on raw truth.

How we do it

The gathering of customer stories is the first stage of our design process and we have three main ways of doing it.

1. Full immersion

The first is to go to where our clients’ customers live, work, or play, and to watch them doing, and talking about, the living, working, or playing. It’s as simple (and involved) as that. We immerse ourselves in people’s activities by temporarily inserting ourselves into their homes or workplaces, and we see what they do in the real context of their lives. This means that we witness what they actually do, rather than what they say they do, what they’d like to do, what they usually do, or what they might do. So if we’re in an airport, for instance, we see airport work happening and can even try it out for ourselves to experience what it’s like. We might walk past baggage handlers sleeping on piles of luggage, and when they wake up, ask them about how their night shift went (and we really did!). That’s the value of being in the place.

This is especially true of someone’s home. Think for a moment about your own home; walk through it in your head and try to see it as a visitor might. Don’t clean up—just leave it as it is. What would your guest be confronted with? Artwork on the walls? Children’s toys? TVs, books, plates, and papers? Think of the clues that point to the kind of person you are.

When I—Jon—see my own home through the eyes of a guest, I visualize a beautiful kitchen in the center. I imagine that the people who live here find comfort in domesticity and in creativity around food. It looks like something out of a magazine, and it must be a point of pride—I bet those people entertain in that room because they think that it represents them. But when I look a little closer I see a few dishes in the sink and a bit of dust under the cabinets. I look even more closely and spot some paint chipped on the lower cabinets, and a dog dish with crumbs scattered around. I see a stack of mail, bills, and catalogs on the counter.

This is a theme of my home: a beautiful place of comfort that my wife and I are deeply proud of, but with signs of being slightly ignored. We clean regularly but haphazardly, and we’re busy—the stacks of papers and books are things we haven’t gotten around to. We have no television, and we’re proud of abstaining from popular culture, yet we have tablets and computers for social media. We eat healthy food and let everyone know it—but I also drink an awful lot of beer. Probably too much.

Home is an interesting mix of aspiration and reality. Many of us surround ourselves with the things that we feel best represent ourselves to other people, but also with what we’re most comfortable with. A home is full of details and clues that are about as honest a glimpse into a person’s self (and presentation of self) as we can find. It follows that when we’re invited into the home of a research participant, we see both how they want to be viewed and how they really are.

Naturally it’s a privilege to be invited into someone’s home or workplace and we don’t take it for granted. Our approach is that the inhabitants are the experts on their own lives and we’re the apprentices. Raymond is an expert drug provider; Judith is an expert chainsaw remover. We’re always considerate, curious, and non-judgmental; this helps them to relax around us, and for us to see the world through their eyes.

You’d be surprised at how comfortable people are with us looking around their living spaces, and how much they’re willing to show and tell us. We can also go through their private possessions and ask questions about them. If we’re talking to them about their taxes, for instance, we can ask if they would show us their most recent returns. We see them rooting around in their filing cabinets, shuffling through the piles of paper on their dining tables, or heading straight to a file on their bookshelf. We’re now realizing the seriousness, or lack of it, with which they treat these things. Similarly, if we’re talking to people about education we can ask to see their homework assignments, log onto their computer and try out their online learning tools, and accompany them to one of their classes.

Through this, we learn some surprising things. One of our clients was a manufacturer of a special kind of TV remote control, so to learn more about how people use remote controls we went into families’ homes to look at their kids watching TV. We hung around their living rooms and saw the kids fight over who got to hold the remote—activities you might expect. But we also realized that the kids were messaging each other on their phones while they were sitting beside each other on the couch. We would never have thought to ask a child, “Hey, do you text your sister while you’re sitting a foot away from her?” But that’s what happened, and we included it in the story that we told about their lives.

2. Video journals

The second method we use to discover stories is video journals. Sometimes, before we visit our participants, we give them activities to carry out and a way of recording them. The resulting footage can be anything from 30 seconds to five minutes long.

For instance, we worked with a life insurance company that wanted to better understand how people purchased its product. So we said to the research participants: “On the first day we’d like you to record yourself learning about life insurance. On the second day we want you to find three providers. And by the end of the week we’d like you to go through the process of buying the insurance, all the way until you have to pay.” The videos gave us a level of intimacy with what they did that we’d never have been able to achieve by asking them about it in theory. And when we visited them at home afterwards, we could question them about what they’d recorded.

Again, we witnessed some surprising activities. On video, we watched a guy researching the term life insurance on his phone while pounding the treadmill at the gym. When we showed the footage to the executives at the life insurance company, they were astounded. They assumed that people treated buying life insurance as a serious business, sitting down with their partner to talk about how much coverage they needed and pondering what financial legacy they wanted to leave. Whereas this guy carried out the activity while ramping up his step count.

The fact that this was captured on video made a huge difference.

“Did this really happen?” the executives asked.

“It did,” we replied.

“Okay, but he must be an anomaly.”

“Maybe he is. But he’s a prospective customer.”

“How could he do that? It doesn’t make sense.”

It didn’t make sense to them because it didn’t match the picture of a prospective customer that they’d built in their minds, but it made perfect sense to our participant. Why wouldn’t he buy insurance at the gym, when he had some spare time with nothing else to do?

Our research for a real estate company revealed another way that timelines and videos help us to understand people’s lives. Our client wanted to learn more about how renters go through the decision-making process of buying a house instead of continuing to rent. In the mind of the company executives, it was a linear exercise: a renter does their research about buying, chooses a property, then buys it. However, by asking renters to video themselves over time, we prompted the executives to think of the process as being more fluid and ambiguous than that. The renters might ask themselves in November if they should renew their lease in January, or look to buy a place instead. Then they would look at mortgages, start to worry about the commitment, and decide to carry on renting. In June or July they might catch the bug to buy again, and then abandon the process until November rolled around once more.

When we presented this to the real estate executives, they found that the difference between what they’d expected and what actually happened was uncomfortable for them. But the videos from the participants proved to them that their potential customers really did think this way about real estate.

3. Worksheets and activities

The third method we use is to ask people to fill in worksheets, the most common of which is a timeline. If we want to discover what someone thinks about their education, for instance, we obviously can’t sit with them all the way from elementary school until they get their PhD. But we can ask them to complete a timeline and write down key steps. Of course, what someone thinks of as a “step” is unique to them, as is the place from which they choose to start. Some people begin their education timeline at kindergarten and others only the week before our conversation, because that was the most significant stage for them.

After the participants have written down their steps, we ask them to go through each one and tell us whether they were happy or sad at the time, and why. This isn’t the same as watching their behavior when it happened, but it’s a lot more “real” than asking them to talk about it in theory. What’s most interesting to us are the experiences they choose to highlight, because they’re the ones that stand out for them. And by questioning them about those experiences in person, we can get into the detail and the richness of their situations.

These research methods are hard and time-consuming—it would be much easier for us to carry out quantitative surveys or a focus group with 10 people at once. But the value of in-context research is that we aren’t simply an information-transferring device from consumer to client, but the author of a point of view that comes from a rich immersion in their customers’ lived experiences. For this reason, we bring our clients into the field with us so they can experience everything first-hand for themselves. And we stay in continuous conversation throughout and debrief with them immediately afterwards. This is important, not just for their learning but also for them to be able to sell the research findings internally to other stakeholders. They have to believe that what the research participants did really happened, and the best way for them to trust it is for them to see it with their own eyes.

What this kind of storytelling is not

If this way of gaining intelligence about your customers is new to you, it can seem as if it has some pieces missing. And it does—deliberately so. I’ll address the two main ones here.

Storytelling is provocative, not predictive

The most common feedback we hear when we present our research to our clients is: “This is all very interesting, but these stories aren’t representative of our customers’ experiences across the board. They’re anomalies.” And what we tell them is that they may be and they may not be—that’s not the point. Our goal isn’t to talk to 20 people and extrapolate what we learn from them into thousands of people. Our goal is to talk to 20 people and use what we learn as inspiration for making new things—for designing new products, new capabilities, and new ways of seeing the market. It’s about provocation, not prediction.

What we find time and again, though, is that when we tell the stories to our clients, they resonate. Sometimes it’s because they’re ridiculous or outlandish, and sometimes it’s because our clients can see bits and pieces of their own experiences in the narratives. But when they resonate, the stories become sticky. They evolve into a centerpiece for the business conversations that follow.

Participants are not personas

You probably know what a persona is: it’s a short description of a composite character that’s designed to represent a group of customers. Personas have become popular in marketing and product design because they’re seen as a practical aid to ensuring that products are aimed at the right people. For instance, one of our clients created a persona with the unfortunate name “No-Lunch Nancy.” Amongst other things, she was so busy that she never had time for lunch; she worked out three times a week at her local gym; and she had a dog.

For us, personas are a waste of time. The intention behind them is to help product designers to make decisions by looking at things through customers’ eyes, but this can be misleading because the personas are fictional and thin. Instead of the rich substance of Raymond and his experiences in jail and on the streets, they offer only a one-dimensional, made-up caricature. As such, personas have little substance and are rarely inspiring.

In fact, the point of the stories we gather is that they’re not typical of a “standard” customer. We celebrate the participants’ idiosyncrasies rather than smoothing them out. It’s through the quirks that we see bigger truths—that people can make mistakes about what they try to carry onto planes, or that there are those who know a lot less about finance than banks might think. If you have time available to explore who your customers are, my suggestion is not to create personas. Instead, go talk to five people who use your product. Just hang out with them for a while and see what you learn.

In exploring the power of stories, we’ve touched on the impact they have on our emotions. This is a crucial element of their effectiveness, and is why the next chapter will explain how stories bypass our logical side and reach straight to the heart.